Want to Learn More?

I’m hosting a live Botanic Bootcamp session, Reading the Land for Smarter Planting, on Monday, February 2 at 6 pm CST. You’ll learn how to read a site before you ever pick a plant. We’ll discuss seeing visual and experiential aspects, understanding light, soil, and water, and more so your plantings are more resilient, intentional, and purposeful. This session will give you the framework to make better planting decisions from the start.

What does it mean to read the land? To me it starts with taking account of everything that is present and to imagine what the site can become.

Reading the land requires us to have two ways of seeing the landscape, what does the landscape offer and what potential does it have. We call these two mental modes inventory and analysis.

Sure, this process isn’t as glamorous as picking what plants to grow and how to arrange them. Often we want to rush into design, but doing inventory and analysis first can save you so much headache later on. We can prevent plant death and replanting, blocked views, flooded beds, wasted money, constant maintenance, and much more. And it doesn’t have to be a new garden that you are assessing. It could be one that you’ve lived in for twenty years.

Thrash Early

Inventory and analysis are part of the process that Seth Godin calls thrashing, where we get things right early in a project. We take stock of what we have and what direction we want it to head. We bring everyone in on a discussion to make decisions early. For some, it may be a husband-wife team. For others, it’s multiple stakeholders and people from the public. However, it is better to thrash early than wait until the project is 95% finished to realize we missed something.

Site Inventory

With inventory, we are asking what is present. It is objective, descriptive, and observational. We are making no judgments yet. Just the facts, ma'am.

For me, site inventory breaks down into six categories:

Physical — buildings, hardscape, utilities, topography, geology

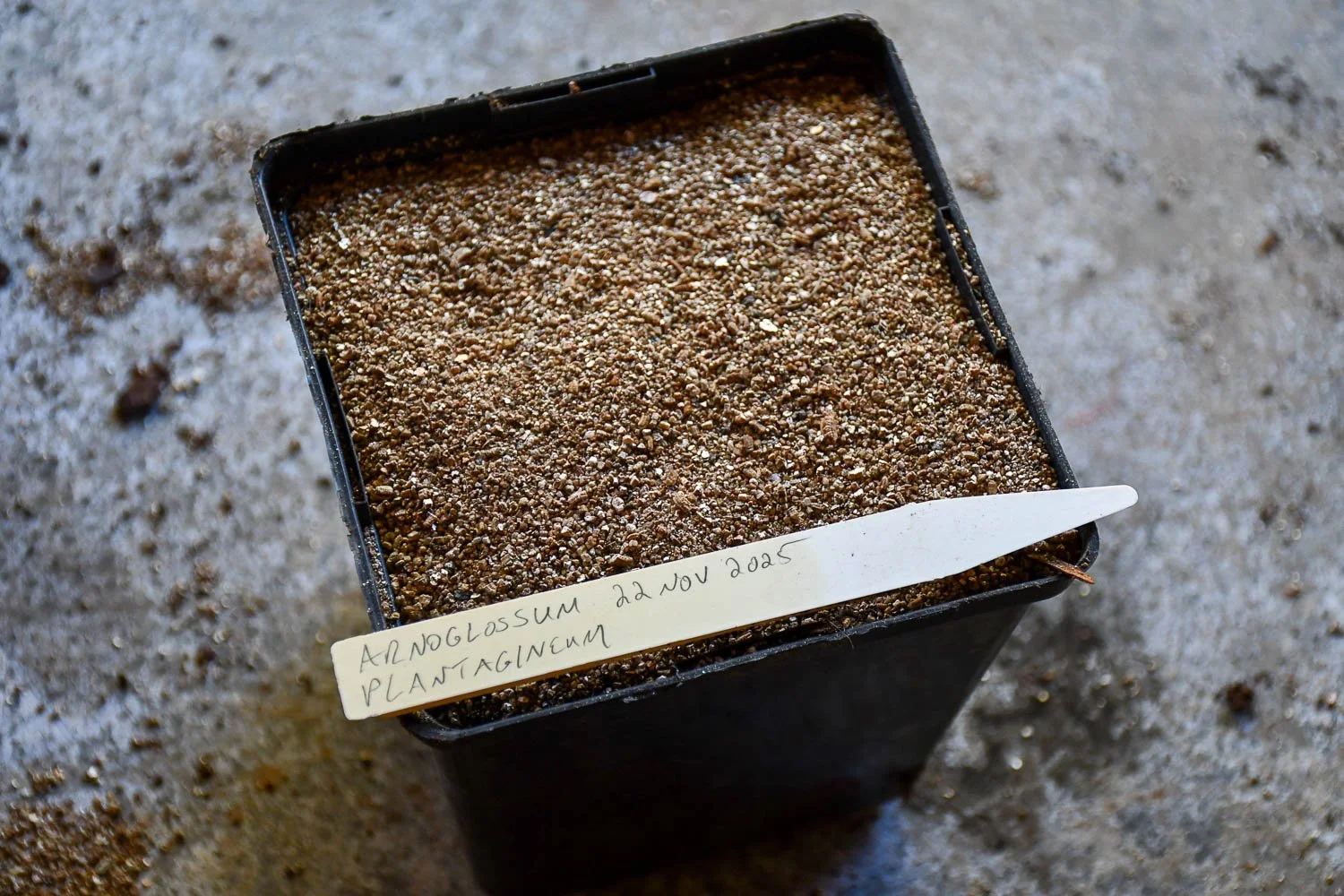

Biological — flora and even fauna on site, where types of plants congregate, plant communities

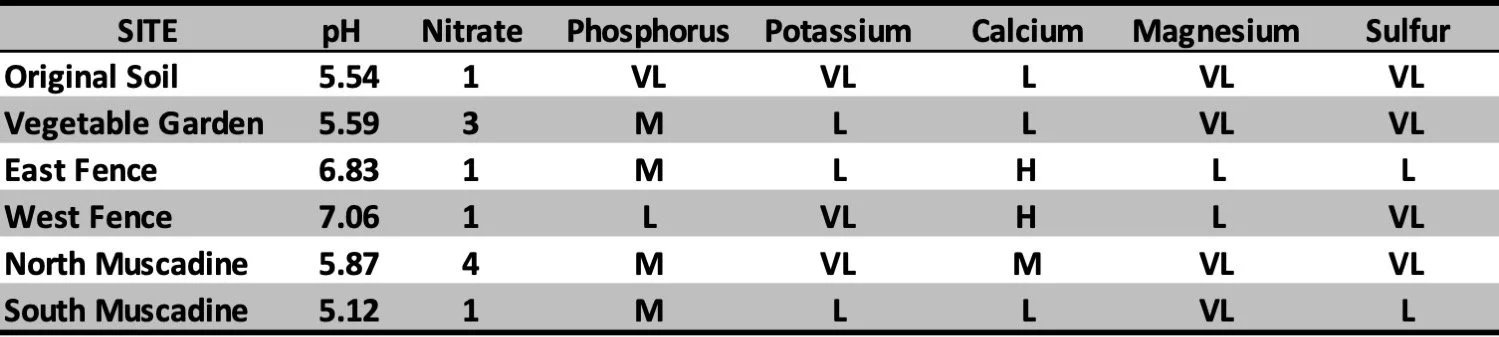

Soil — soil texture, soil drainage, soil nutrient levels and pH

Weather and climate — temperature, rainfall and where water pools, wind movement across a site, microclimates, where things feel warmer or cooler

Light — how it shifts over the day and over the season, sun angle and reflection

Visual and experiential — vistas and long views, the mood of the site, the spirit of place, and natural movement paths

Site Analysis

With the inventory complete, we begin the analysis to consider what this place can be. What can I do with this space? Analysis is interpretive, evaluative, and creative. We begin to introduce goals and priorities, and we begin to see the site through human desires and wishes. We start considering constraints and opportunities and can we work with things or will we need to move against what we see.

I should stress that analysis is not design yet. There are no plant lists, layouts, or styles decided on yet. You are just trying to see what you can do with the possibilities and constraints of the site.

So, just a few ideas for the same six categories

Physical — Do you hide or accent the house? Are there places for more entertaining options? What does the lay of the land dictate about movement or erosion?

Biological — Should trees stay or go? Does the vegetation have a natural tendency toward an archetype? Should it be allowed to progress or interrupted? Are there plant communities, animals, or ecological processes that need to be accounted for?

Soil — How can soil fertility and texture influence what plants grow? What can we do with high fertility or low fertility? Does soil drain well or is it mucky?

Weather and climate — What does it mean that this microclimate is warmer or cooler? Should we plant species that will move with the wind, or do we need a wind break to calm the air?

Light — How can you play with light? Do you want more light or less light?

Visual and experiential — Are there potential views you can create or enhance? What can you do to create feelings of prospect and refuge? What are the landscape preferences that we can embrace and enhance in the space?

Analysis isn’t limited to one idea. It may be worthwhile iterating through options to consider what all possibilities exist. For example, when we bought our property, we had a large open space beside our house that could have become anything. I could have planted a vegetable garden, more trees for shade, or an orchard.

I noted the space’s proximity to the house, the sandy soil, how water moved across it, and how it wasn’t saturated like other parts of the property. It was mostly turf, which meant that it was ripe for planting. Light would interact with it throughout the seasons and for most of the day. Being in an elevated spot, it offered good views of other parts of the property, and I didn’t want to interrupt that. I knew I wanted a naturalistic planting, and inventory and analysis helped me reach the conclusion that this spot was perfect. Even when I consider any changes to the garden, I keep these initial observations and ideas in mind.

Our blank slate of a yard in 2017. It took me time to read the land, to inventory what we had, and to analyze and think about what I wanted this space to become.

Several years later, here’s what I get to look at. It all starts with inventory and analysis.

Conducting Your Inventory and Analysis

Doing your own inventory and analysis is easy. You can easily take some blank paper and sketch what you see. Or, find the place on Google Maps, capture a screen shot, paste it into PowerPoint, and make the image 50% transparent. Then you can print off a few copies and walk around the site writing or drawing what you see.

You also don’t have to do inventory and analysis just once. You can repeat the process over the course of a year. I know that most designers are under the constraints to only visit once or twice, but it can be hard to truly know a site until you’ve experienced it for a trip around the sun. You don’t know yet where the last light lingers on the winter solstice. Or, how the water moves across the property during a deluge. Time and a few tricks that I’ll discuss in Reading the Land for Smarter Planting will help you.

Remember, inventory describes and analysis decides. And, once you’re done, the magic can begin as you start to create the garden of your dreams.