“I want to look at a plant coming up here in a second,” I said to Karen as she drove down the road.

“Ok,” she replied.

20 seconds later I said, “Ok, here it is. Pull over at this road.”

“What!?!” She replied going 70 mph. “This soon?” Of course, she missed the turn because of my poor communication, and we had to go down and come back to find the plant.

And, then she safely pulled off onto a side road as she probably wondered why she couldn’t have married an accountant instead.

Such are the adventures of living life with a horticulturist.

There in the right of way was a large clump of a plant I had never seen before. A year ago as we were driving to Tennessee in late May with Karen at the wheel again, I noticed this large clump of white flowers on the side of the road. With the quick glance at 70 mph, I noted it looked like a Penstemon digitalis (foxglove beardtongue), but since mine had finished blooming, it had to be something else since this plant was in full bloom. I recalled colleagues sharing photos on Instagram of a white blooming Physostegia around this time of the year. A quick glance at iNaturalist showed a species nearby, Physostegia angustifolia. But, I would have to get out and investigate further to confirm. By this point we were too far down the road. I grabbed a quick screenshot on my Compass app to note the location. I figured we would be back this way again sometime in late May.

A year later, I could confirm it was indeed Physostegia angustifolia, also known as narrow-leaf obedient plant, or to a certain playful spouse as the marital strife plant for reasons you can surmise from above.

One of my favorite aspects of native plants is that we can actually go nearby in the wilds to see where they grow. And, even more fun is discovering new ones. Normally, I like to grow plants for a bit before I feature them on the blog, but I realized that this encounter would be the perfect time to share a simple approach that I use when I meet a new plant in the wild.

We use a scale to measure mass in science, and I use the acronym SCALE—site, character, association, lens, and envision—to assess a plant’s essence in the wild. It’s a field-based acronym I use for learning about a plant in its native habitat.

SITE: Where does it grow? Make observations about the soil, light, moisture, slope, and surrounding area. Here it was in a mesic flat spot in full sun. I would have to take a soil test to learn more about the nutritional status, but from looking around other plants were growing well.

CHARACTER: What does it look like? Note the form, texture, bloom, and structure. Also consider what else do you know about the genus or family that helps you understand the character. Physostegia are in the mint family, thus explaining the large group and the square stems with opposite leaves. I noted the narrow leaves, hence the epithet angustifolia, which means narrow-leaved. They had an upright, fine-textured form that blended in well with the grass. And, the flowers were lovely. In the grassy right of way, their white blooms nodded and looked like little wedding dresses as they waved in the breeze. I didn’t notice much of a fragrance. My guess was the plant has spread via rhizomes, and it was likely all one clone.

ASSOCIATIONS: What role does it play in its environment? What other plants are nearby? And, does it have any connections with other species? I noticed that nearby were other east Texas species like pines, poison ivy, and sweetgum. I also saw bees were visiting the flowers. These observations can start to give you a sense of the ecological role it might serve.

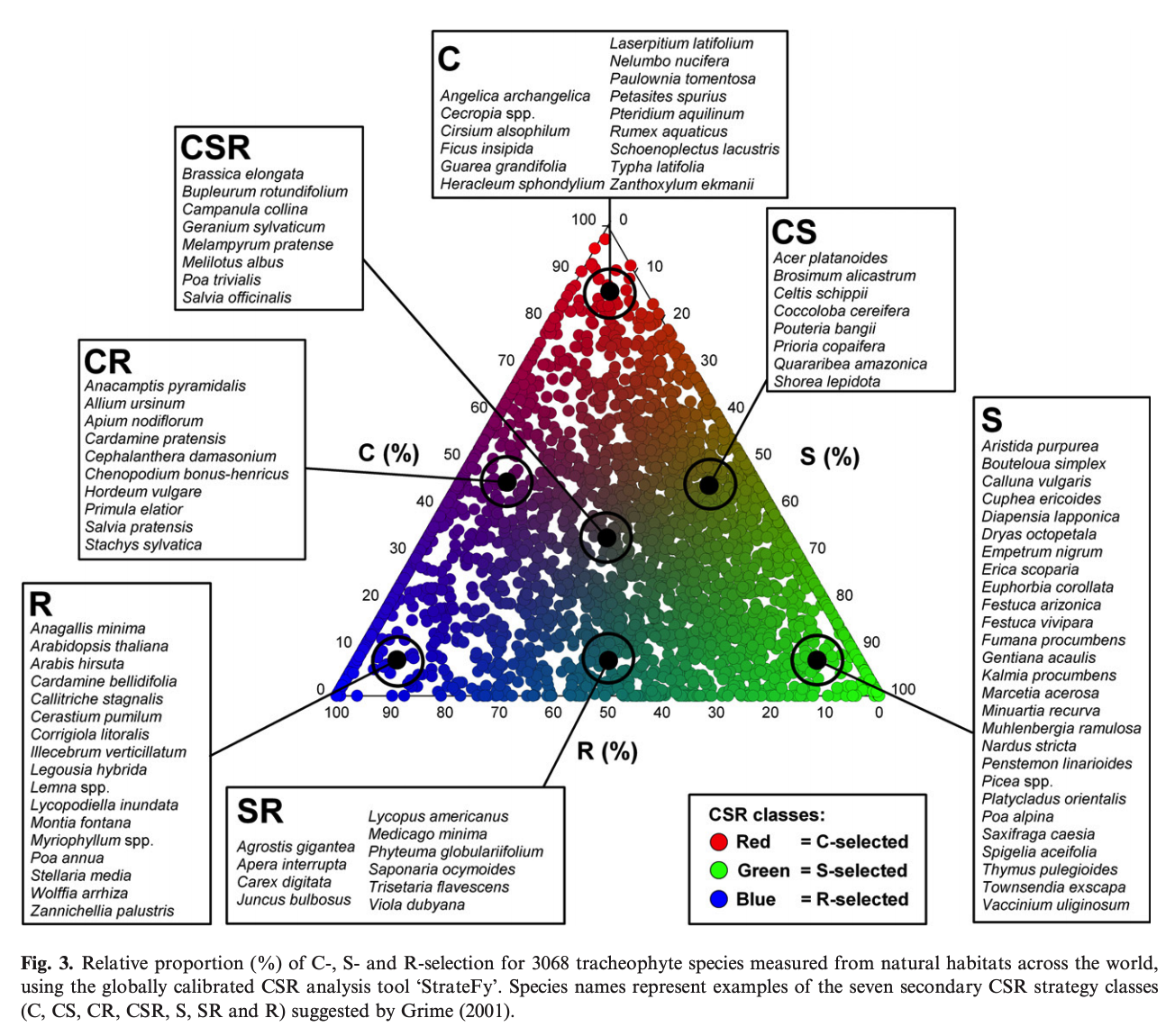

LENS: What lens or models like Grime’s Triangle, sociability, and plant layers help you visualize how it grows? The clump was quite large, maybe 15 × 15 ft wide, so clearly it had some competitive tendencies which led to a high sociability value. And, it would likely be a seasonal filler in its role.

ENVISION: Last, ask how you can envision it in plantings. Is it worth trialing to further observe how it performs before using it large scale? Do you need to understand the phenology and seasonal behavior? I felt this Physostegia is another wonderful option as I look for candidates to help fill this gap that we encounter in late may and early June as we lose the spring flush and summer plantings start to take hold. My guess is since it is blooming so early, it would likely be dormant by later in the year. And, since the thin leaves hide in grass, using it in a grassy area would help to fill the gap it might leave. And, it would likely need some disturbance to help keep the rhizomes under control.

I feel like some caveats need to be mentioned for stopping alongside a road. Make sure you’re safely off the road. My preference is to find a safe pull off or side road where parking is an option. Be conscientious you are not damaging plant populations, and be aware of any laws regarding plant collecting or trespassing.

I left confident that I had found a new-to-me species to use in naturalistic plantings here in the southeast. SCALE helped me quickly make sense of its identity and its potential.

And, I left promising to buy Karen some coffee to patch things up. The wild has so much to teach us if we have a little curiosity and a patient co-pilot.