This semester, one of the classes I’m teaching is herbaceous plants, and I’m taking the class beyond the usual discussions of annuals and perennials. From studying herbaceous plant communities, one of the most useful concepts that I’ve learned in recent years is the classification of a plant’s survival strategies.

I’ve written about it before here and here. As a refresher, Grime pitched that plants had three strategies based on environmental factors.

COMPETITORS are plants that take advantages of any and all resources they can muster. They grow tall and wide to take out the competition. Usually these stalwarts are perennial in nature, and they grow where stress and disturbance are nil.

STRESS-TOLERATORS are plants that have adaptations to ensure survival when stress arises and conditions deteriorate. They are usually perennial and can take many years to flower from seed.

RUDERALS are short-lived annuals or biennials that are frequently exposed to some type of disturbance, which has selected for plants that quickly produce seed.

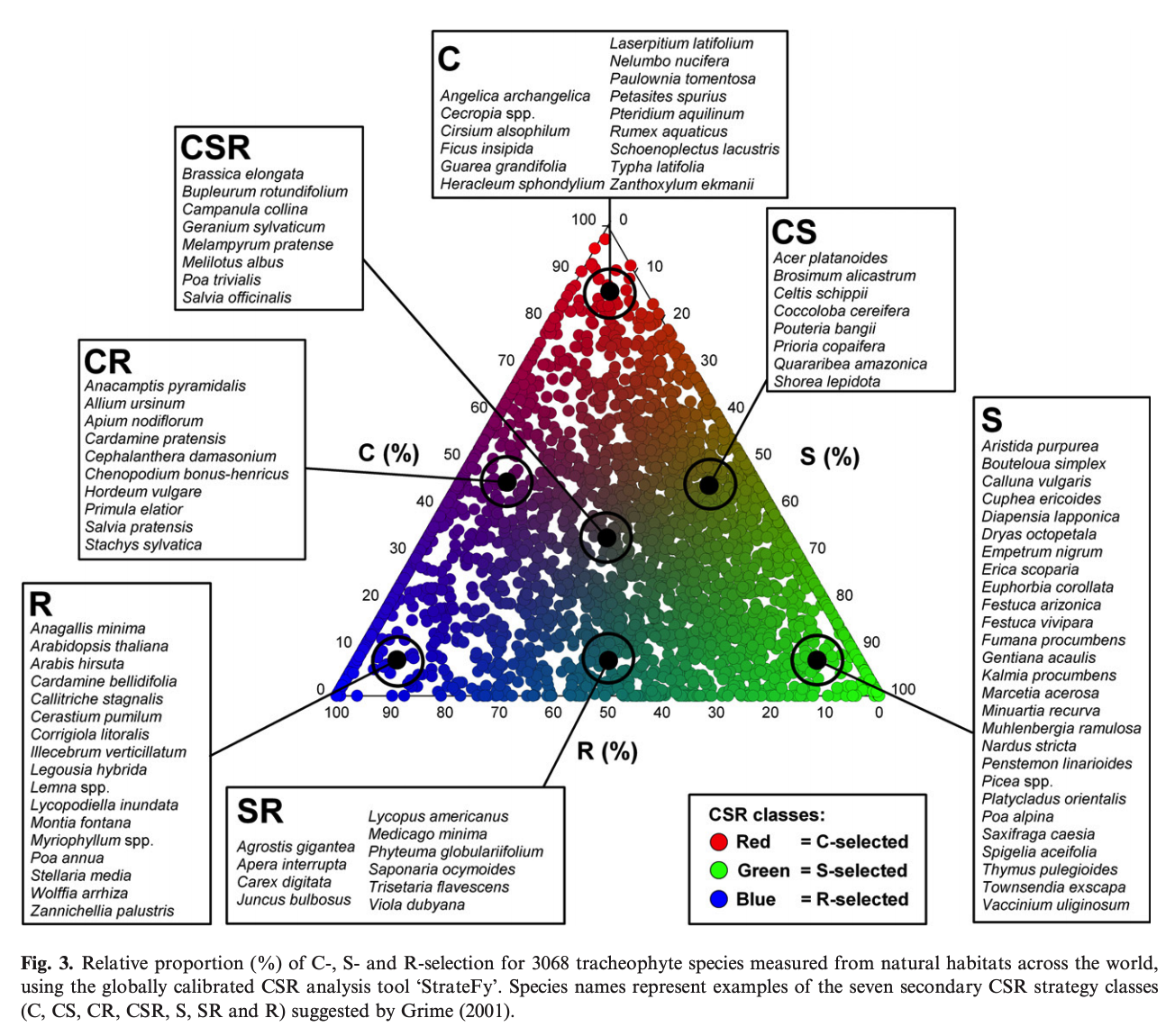

Usually, this strategy is visualized using a triangle (much like the soil texture triangle!) where a certain species can be shown to be—pulling some numbers out of the air—say, 70% competitor, 20% ruderal, and 10% stress tolerator based on the characteristics they exhibit.

A figure of Grime’s triangle from Pierre et al. (2017) titled A global method for calculating plant CSR ecological strategies applied across biomes world-wide. As you can see the authors attempted to classify plants across the globe based on their tendency to be a competitor, stress-tolerator, or ruderal.

How do you take this concept from theory to application for students? Much research and data collection is needed to be able to precisely place a plant on the triangle. Can it be done in a more simple fashion?

After we covered the CSR theory in class, I did an activity with students. I gave small groups (three to four) a list of seven different herbaceous plants and asked them to look up information and pictures online and try to determine where on Grime’s triangle it would fit. I drew a triangle on the board labeling the sides and gave them markers and half sheets of paper for writing plant names.

I then challenged them in pin-the-tail-on-the-donkey fashion (no blindfolds or sharp objects though!) to figure out where on the triangle the species would go by searching for it online. Students looked for tendencies to spread, cover large areas, form large clumps, and/or have rhizomes (COMPETITOR); tendencies to produce copious amounts of seed, occur in areas of disturbance, and/or be short lived (RUDERAL); and tendencies to live in a stressful habitat, take a long time to flower, and/or have storage organs (STRESS-TOLERATOR).

One by one they started coming up and making educated guesses. I stood by the triangle to offer advice and suggestions. Some hit the nail on the head while others needed a little bit of coaxing to the right place.

At the end, we went over the 20 or so species I provided as a challenge. Again, I explained that while some species neatly fit into one group, some straddle the fence like Liatris elegans. It has a corm (a stem-derived storage organ indicating some level of stress toleration) yet produces copious amounts of seed (traits of a ruderal).

Pin the plant on the triangle—a fun game to teach students about plant survival strategies. Based on your plant knowledge, how do you think they did?

As gardeners it’s very helpful to think about flora in this way. It helps us anticipate how plants will perform. It explains why Gaillardia and Aquilegia don’t live long as perennials (ruderals), why Mentha and Monarda spread like crazy (competitors), and why Trillium and Narcissus take 3–7 years to flower from seed (stress-tolerators). It also allows us to envision how to combine plants. Maybe put that runaway competitor in a drier spot to keep it from taking over creation? Or, sow some ruderals in between the stress-tolerators to keep weeds down.

If students can decide approximately which section of the triangle plants fit in during a 15 minute activity using search engines, then we can by watching how plants grow over the course of a year.

So, that’s your homework for the season. Draw a triangle and see if you can’t plot where the species in your garden fit.