I’ve deemed this time of the year Sowvember. It’s like the Dog Days or Inktober, but this season is for propagating all those seed you want for next year. What I love about Sowvember is that it asks very little of you. You spend a few minutes with a tray, a handful of seed you’ve collected, and the willingness to work with the season.

Sowvember is when I sow most of my perennials so they can stratify as needed over the winter. It has no official beginning or end, but usually it runs from first frost through the middle of January when the garden rests. It differs from spring sowing where we are gearing up for the coming gardening season. With spring we are worried about warmth.

With the season of Sowvember, we relish the darker side of the calendar and take advantage of the natural cool and moist conditions needed for stratification. Sure, I augment from the hose as necessary. But, following the natural tendency of the season makes life easier.

My goal with sowing seeds is to grow as many of the best plants I can using simple methods. I have a full-time job, and I’m a dad. Complicated schedules and tedious details don’t work for me. So, I find myself optimizing for efficiency. I can check on my seedlings every few days instead of the intensive watch I have to keep on plants during the spring and summer. While I could wait until later to sow the seed and use the fridge, I’ve learned for us in the South some species will germinate in the winter to begin their growth, and already I’m seeing cotyledons on some species I started earlier this month.

There’s also an abundance of seed at this time of the year. Sure, some of that abundance comes from the backlog of bags, envelopes, bowls, boxes, and old medicine bottles that litter my office with seeds collected from this year. Those I try to sow first, especially any ruderal or short-lived species that germinate during the winter. But, Sowvember is also the last chance I have of getting seed before they fall to the ground, fly on the wind, or vanish for a bird’s or a mouse’s meal. I’ve learned the sooner the better on collecting seed, and if the thought crosses my mind that I’ll collect those seed tomorrow, it’s probably best to do it right then.

My garden is a continual source once I get a species established. I’m trying to be better about keeping brown lunch bags in the garage so they are ready to capture plant progeny at a moment’s notice. Often, I’ll cut a stem off and flip it upside down in a bag to finish dislodging the seed over a few days. And, then I’ll give the bag a good shake. Any remaining stems I’ll beat over the garden for seed to come up wild. I’m sure the neighbors think I’m doing a séance over my beds.

It’s a conundrum in the garden. How long do I leave the Liatris aspera (rough blazing star) seed on the plant to enjoy before harvesting?

Sometimes during Sowvember I go into the wild to glean. I went out the other afternoon and collected seed on some back roads for more native grasses at Ephemera Farm. I was mainly hunting Tridens flavus (purpletop) and Andropogon ternarius (split-beard bluestem, header image), and I had already filed away a few spots that the mower had missed. I sat a cardboard box down beside me, grabbed the culm just below the seed, ran my gloved hand up, and released the seed into the container. After a few minutes I had a decent handful or two of seed for sowing. I try not to be too greedy, and like manna in the wilderness, I collect just enough for me.

The frilly pappi of Andropogon ternarius (split-beard bluestem) glow in the late afternoon light.

Once I’m ready to sow seed, I am thoughtful as decisions now can make the process much smoother. I consider what plants I need for the coming growing season. What projects do I have where I need to grow my own? What plants have been in decline that I need more of?

It is also worth considering what type of tray or pot to use. Reliable germinators like Penstemon tenuis (Gulf Coast beardtongue), Streptanthus maculatus (clasping jewelflower), and Echinacea purpurea (purple coneflower) I do in 50-cell Winstrip trays. I bought them initially for their durability, but in the off season, they also are great for starting perennials. Other than my Winstrip trays, all other trays are recycled from plants I’ve gotten. My favorites are the deeper 50-, 38-, or 32-cell trays. Smaller cell trays like 72’s or 144’s work, too, but having that extra substrate volume gives me a little more flexibility on catching plants before they dry out too much. I also use community flats that have no cells for species that have staggered germination like Carex cherokeensis (Cherokee sedge). I tease them out once they get to a certain size.

An intersection of Winstrip trays on the nursery bench. Clockwise from the top left: Streptanthus maculatus (clasping jewelflower) already have true leaves; they just need a bit of thinning. Recently collected Helianthus radula (rayless sunflower) are dusted with vermiculite to aid germination. And, the tiniest seedlings of Penstemon tenuis (Gulf Coast beardtongue) are just sprouting.

If a species is new to me, I’ll usually sow it in a small pot and tease the seedlings out later. I’d rather have a small amount of substrate invested if I only have one seedling germinate. However, if it is a deeper rooted species like Asclepias (milkweed), I will go ahead and sow seed in a gallon pot. That way the roots don’t rot in the shallow cell. I don’t use milk jugs like friends further north do. We have too many warm days in winter for them to be able to vent the heat well. And, I’ll hit seedlings with a weaker fertilizer every so often. I find that rain during the winter can leach nutrients out.

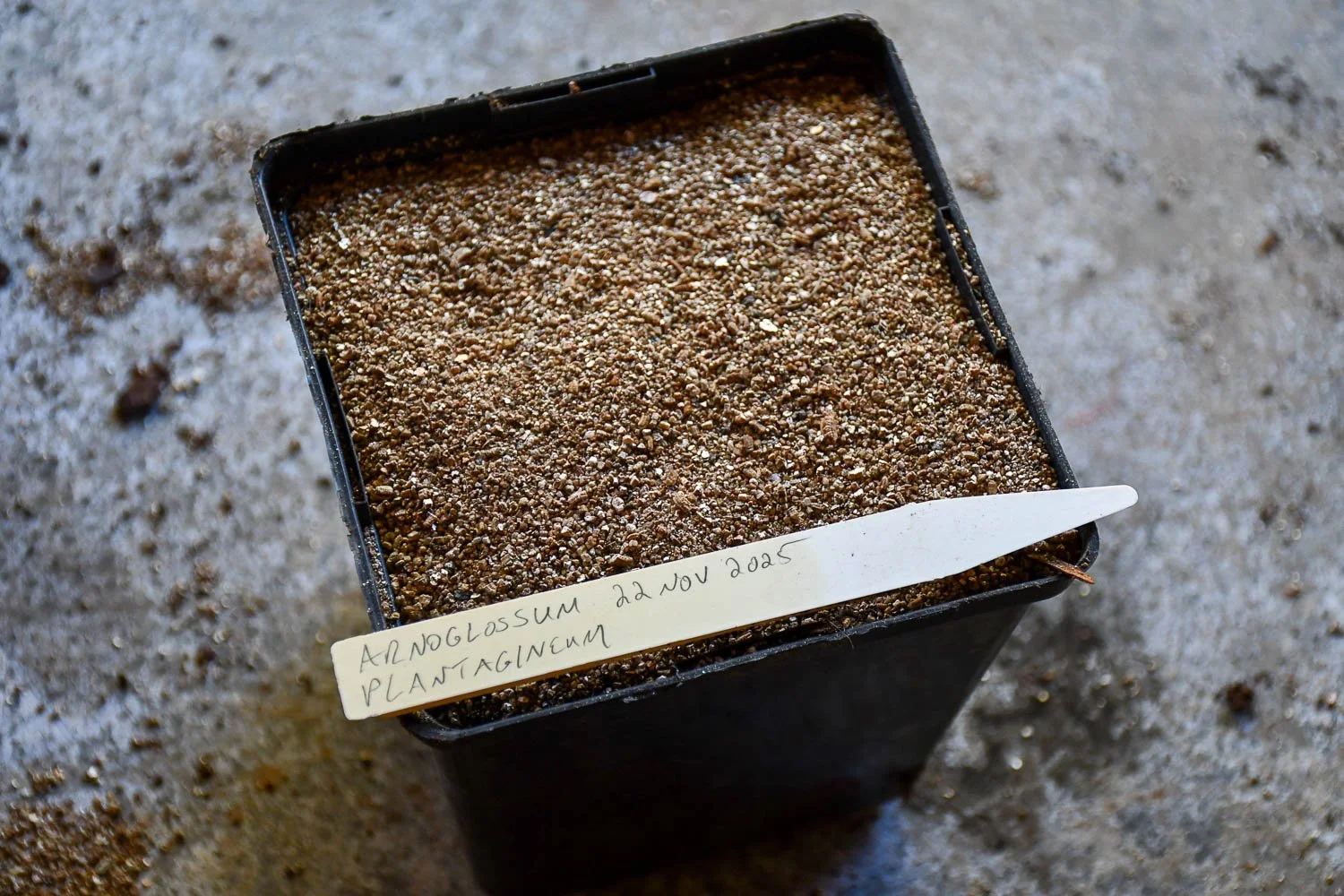

Arnoglossum plantagineum (prairie Indian plantain) sown in a larger pot. Once the seedlings germinate, I can tease them apart and pot them into larger containers.

The last thing I watch with seed is the temperature because it’s as likely to be 8°F as it is to be 80°F in December. If conditions get too cold, I’ll throw a tarp or blanket over them to make sure they stay warm enough. I used to bring them in the garage; however, I’ve learned our native perennial seedlings are tough. Most can easily tolerate a light freeze.

I hope you’ll celebrate Sowvember, too. You’ll love how small, steady efforts now will pay off big when you (and I!) have plenty of seedlings come spring. If you need more help, my class Success with Seed Sowing will get you growing in the right direction.